Why Desperate People Are Suing Immigration Canada

Long delays, a lack of information and poor service are bringing a spike in court actions over agency’s failures.

From January to the end of February, Alejandro Ginares woke up daily at 6 a.m. in order to grab a spot in the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada phone queue.

He went about the business of his day — preparing breakfast, doing dishes and feeding his cat — until eventually, sometimes after eight hours of being on hold, he’d reach the front of the queue and receive a pre-recorded message: “all our agents are busy, try again later.” He’d hang up. If it was early he’d try again. If it was after 3 p.m., when the offices out east close, he’d make dinner, go to bed and start all over again the next day.

While news articles have been filled with stories of long lineups of Canadians stymied while renewing passports, less has been reported on how the pandemic and its knock-on effects have impacted would-be Canadians, whose immigration applications have been left in a backlog that has only increased since the beginning of the pandemic.

In Ginares’s case, he was desperately trying to track down the status of a permanent residency application he’d submitted 15 months before.

Occasionally he’d reach a human being, only to be told that his application was “not in the system.” He was baffled. He had paid the processing fee and had a Canada Post delivery confirmation in hand, certifying that the application had arrived at IRCC. He knew they’d received it. So why wasn’t he in the system?

Ginares eventually reached an agent who promised to help him. A few days later he got a response confirming for certain that his application had not entered the system.

It was then that he realized that IRCC had most likely lost his application.

“It’s awful to be waiting,” he says. “We don’t know if we’re waiting for a purpose or if we’re waiting for nothing.”

Resubmitting his application was risky. It would mean starting all over again. And it would cost another $1,000. He didn’t know what to do.

A geological engineer in Uruguay, Ginares had left his home and family to join his husband, Wendall Seldura, in Canada. The two had met in a cocktail and music bar in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 2017. They’d fallen in love immediately and quickly decided that Canada was the country where they’d spend their future.

Ginares knew that permanent residency processing times can often reach 15 months. But he didn’t think it would take 15 months for the system to even receive his application, or approve a work permit.

Back home, Ginares worked, studied and volunteered. Now he feels like he’s stuck in limbo. “I fight every morning when I wake up to find motivation,” he says.

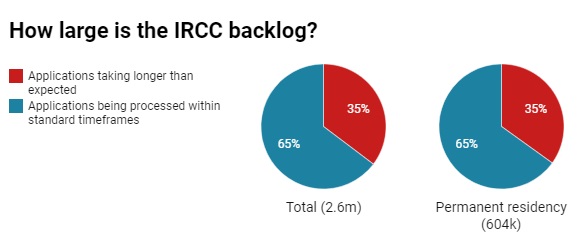

According to data released by IRCC Oct. 31, 2.2 million people are waiting for approval for temporary residence, permanent residence and Canadian citizenship applications. Like Ginares, 1.2 million have waited beyond the standard time expected for their application.

In permanent residency specifically, there are 603,700 applicants. Only 279,700 of these are being processed within standard times; 54 per cent, or 324,000 applications, are not being processed within the times projected by the agency.

B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix recently hit headlines when he called on Ottawa to halt the deportation of Claudia Zamorano, a hospital worker whose family is facing deportation because their applications have not yet been processed.

Nathaniel Preston, Ginares’s immigration consultant, says that he is seeing long wait times for all his clients. His colleagues report the same. “You exist but you don’t. You’re technically not supposed to be here. But maybe you could be here, if they approve the visa, or they restore your status,” he says.

Yet, despite these backlogs, IRCC has not stopped accepting applications. In fact, they are planning to increase immigration rates. Based on the government’s immigration levels plan, released Nov. 1, IRCC will be upping immigration to 500,000 permanent residents by 2025, the highest levels in Canada’s history.

Over 300,000 of these applicants will come through the economic class, with family class, Ginares’s avenue to permanent residency, equaling 118,000. Humanitarian and refugee applicants will equal 72,750 and 8,000 respectively.

Applicants and immigration experts alike worry that IRCC is not working to address the fundamental flaws in its system. They argue that it suffers from a lack of accountability and transparency.

Tackling the backlog

In March 2020, as COVID shuttered businesses across Canada, IRCC closed its warehouses across Eastern Canada to abide by social distancing measures.

This meant that employees could not file paper-based applications. Meanwhile, for months at the start of the pandemic, IRCC continued to solicit applications, according to Kareem El-Assal, managing editor at CIC News and director of policy and digital strategy at CanadaVisa. For example, the Express Entry pool is invite-only. They continued to solicit invites despite the growing backlog, only temporarily pausing in December 2020 and then again in September 2021.

This resulted in a huge backlog that IRCC is still wading through today. The backlog is three times higher than it was prior to the pandemic, according to data obtained by CIC News, an immigration publication.

To tackle these delays, the federal government gave IRCC $85 million in extra funds. According to information provided to The Tyee from IRCC, this fall they also promised $1.6 million over six years to help meet the new 2023-25 immigration levels plan of 500,000 per year.

These funds were intended to speed up applications primarily through digitalization. For example, adopting electronic submissions using technology to interview candidates remotely and implementing “facilitative biometrics measures.”

This digitalization has started with the launch of the permanent resident online portal. A year and a half ago, when Ginares filed his application, it was paper-based and sent to one office. Today, the spousal sponsorship, which is the specific avenue through which Ginares has filed for permanent residency, is digital — meaning the application is not only faster for the applicant, but also that IRCC can shift its workload between offices in order to maximize its capacity. Digitalization also means that IRCC is less likely to lose files.

IRCC has also promised to increase staff numbers. In August, the minister of immigration, refugees and citizenship, Sean Fraser, promised to hire 1,250 new employees by the end of fall, according to a statement provided to The Tyee from IRCC. In September 2020, IRCC also promised that that it would increase the number of decision-makers for spousal sponsorship applications by 66 per cent.

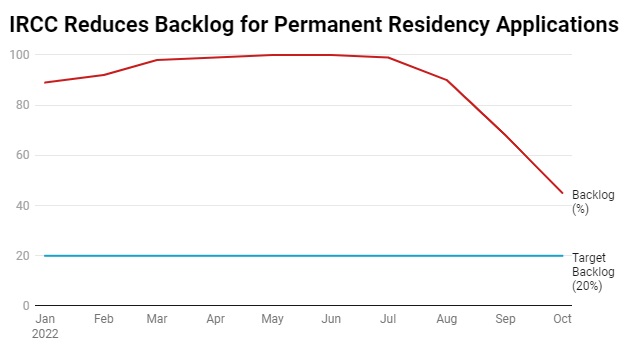

These measures have been successful. According to data provided to The Tyee by IRCC, between January and October, IRCC made decisions on 4.3 million applications for permanent residents, temporary residents and citizens, compared to 2.3 million decisions in the same period last year.

This has decreased the backlog by a significant amount. According to data on IRCC’s website, in July 100 per cent of applications were beyond standard processing times. By October 2022, 45 per cent of applications were beyond standard processing times.

However, Preston thinks that combatting the backlog through staff shortage and digitalization is not enough, especially if IRCC continues to accept more applicants.

“A fixed timeline for when people have to have an answer needs to be put in place,” he says.

Preston isn’t the only one calling for set deadlines.

“I’ve been after these guides for years,” said Richard Kurland, an immigration lawyer who has presented to the parliamentary standing committee on citizenship and immigration and is former special advisor to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

According to Kurland, all other branches of the federal government do have deadlines that they must follow. The deadlines come under the Services Fees Act, whereby federal departments must report to Parliament annually on the fees they charge. These reports should also have “performance standards” that outline how long it will take to provide the service.

These performance standards are decided by the federal department itself and they have no upper limit. When standards are not met, however, fees must be returned.

But when the standards were first introduced in 2004 under the User Fees Act, a measure MPs brought in to control federal departments, IRCC successfully lobbied to exempt themselves.

IRCC does have standard processing times. However, these times are only estimates based on how long it took to process 80 per cent of applications in the past. They are not standards that IRCC can be held to.

If IRCC had performance standards, Ginares would have received an accurate estimate for how long his application would take and, should this estimate not be met, he would be entitled to his money back.

The performance standards wouldn’t only be useful for immigrants. IRCC would also have to abide by deadlines given to Canadian nationals applying for services such as passport renewal.

When The Tyee asked IRCC whether they would consider implementing performance standards, a spokesperson for the department said that the IRCC did provide timelines for most types of applications and that its goal is to process 80 per cent of applications within that timeframe. But these timelines are estimates.

IRCC did not respond to requests about performance standards, and why the agency does not have them.

Kurland believes the reasons why IRCC does not have performance standards are straightforward. “If you tell people it is going to take five years to sponsor a spouse, good luck with that,” said Kurland. “The public won’t accept that. And the Official Opposition, no matter who it is, will say: ‘How come the government needs five years when we did it in two?’”

Kurland also said that it would cost IRCC money when it failed to meet deadlines. And lastly, standard processing times would disincentivize immigration.

Canada’s economy depends on immigration, with the Bank of Canada recognizing that it plays an essential role in the growth of the labour force: in 2017, over one in four working people were immigrants. This percentage is only set to rise as, according to Statistics Canada, nearly one-quarter of the Canadian population is set to age out of the workforce by 2030.

“If you have accurate information you can make better decisions,” Ginares says.

Had IRCC told him it would take five years to get permanent residency, he says he would have applied for residency from Uruguay, not from Canada.

At writs’ end

After Ginares had waited 13 months, his immigration consultant suggested he find a lawyer, who then suggested he use the last tool at his disposal: the court.

In some circumstances, where an application has far exceeded the standard processing time, an applicant can ask the court to send a “writ of mandamus,” which is an order demanding that the government properly fulfil their official duties. The government office responsible must file a response within 21 days.

On Oct. 26, after his lawyer filed a writ, Ginares finally heard back from IRCC. Confirming his suspicions, they acknowledged they had lost his application.

This confirmation, Ginares says, was good news in a way. It means that he can now resubmit an application and the IRCC will begin to process it immediately. When the new application has entered the system, Ginares can anticipate waiting 14 months for it to be processed.

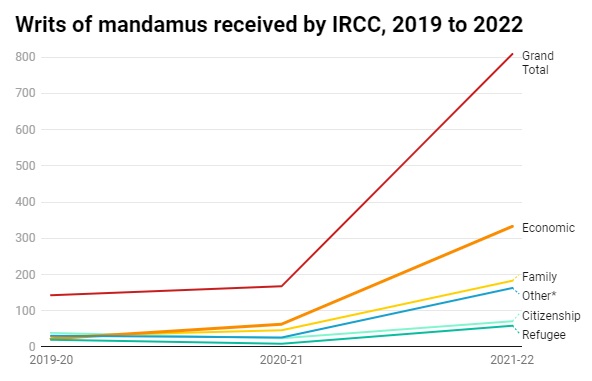

Filing writs of mandamus is an increasingly popular technique right now, says Kurland. This is largely because IRCC fails to communicate with applicants, lawyers and consultants in a meaningful way.

According to data provided to The Tyee by IRCC, writs of mandamus applications have increased five-fold since 2019. In the 2019 fiscal year, a total of 149 writs were filed. From April 2021 to April 2022, 809 writs were filed. Since April 2022, 709 writs have been filed.

But Kurland cautions that mandamuses are a last resort. Not only are they expensive — filing cost Ginares a $1,000 fee plus $1,600 in legal fees — Kurland says they are also a poor use of court resources.

Both Preston and Kurland think that a better solution would be to update the IRCC’s system so that applicants can have fast, online access to the status of their applications.

“There’s a solid business case for allocating resources into improving what a person can see on their own IRCC portal,” said Kurland.

He compares it to the Canadian Revenue Agency, pointing out that the CRA does client service effectively. “With the CRA, you make a couple of calls, you get your info and you get what you need. Client service is not a priority for IRCC,” he says.

Ginares agrees. Recalling those long days spent on the phone, he says he doesn’t consider the remedy from filing a writ of mandamus a great replacement for genuine client service. While his partner was able to financially support him through unemployment and foot the bill for steep legal fees, many others may not be so lucky.

Ginares estimates that his permanent residency application has cost him between $7,000 to $10,000.

“It’s crazy that you have to bring an immigration consultant, a lawyer and the Federal Court into this just to get a meaningful answer from IRCC,” said Ginares.

But, he says, at least now he knows what his next steps will be.

“I can see the light at the end of the tunnel,” he says. “I just hope it’s not a train.”

Source: thetyee.ca