Canada Needs to Build More Housing

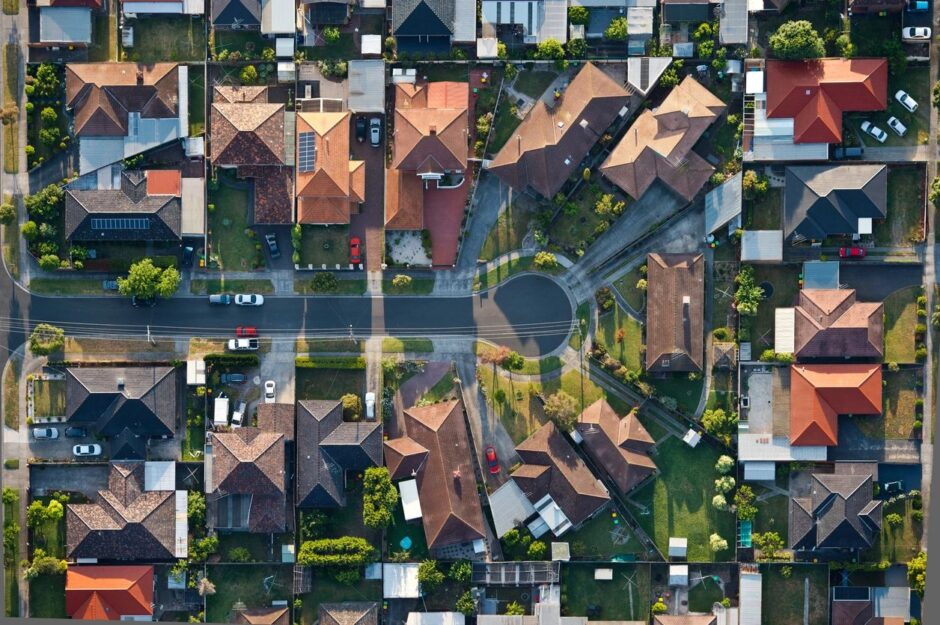

The neighbourhood of West Point Grey in Vancouver, near English Bay and full of multimillion-dollar detached homes, has seen little change for decades, save for ever-higher real estate prices. In 1996, the neighbourhood’s population was 12,885. A quarter century later, in 2021, it was … 12,886.

That no-growth history will soon end. A section of West Point Grey is set to be remade, as development of the Jericho Lands moves forward. It is 90 acres, some of it former government land. Today, it is owned by a coalition of First Nations, the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh. Canada Lands, a Crown corporation, is partner in a portion of the land.

Earlier this month, the group issued a revised development proposal – 13,000 homes in mid- and high-rise buildings. The site would more than double West Point Grey’s population by mid-century.

The extent of the transformation on the Jericho Lands is the sort of scale that can start shifting the equation on Canada’s housing deficit. Over years, the country has dug its housing market into a hole. Strong demand and not enough supply sent prices to buy and rent into the stratosphere.

Climbing out of the housing hole will take years. There are many challenges, including the cost of land and the cost to build. Affordability won’t be restored overnight.

That’s why the quantity of new housing must be the focus. Canada needs much more, and fast. Housing needs to come in a variety of forms, but they must be of increased density. The development of dozens of buildings on the Jericho Lands, for example, with the majority of around 10 storeys high, is one part of the solution. There are other places in Canada with opportunities for rapid growth in urban housing expansion, such as Downsview in Toronto or Confederation Heights in Ottawa.

Such unusually dense developments are a necessary step, but they are not enough to ease the housing crunch. There cannot just be a bunch of towers amid a sea of detached homes, which is the current state in cities such as Toronto and Vancouver.

While there are questions about upping the rate of construction – there are calls to double the number of homes built each year – the housing market has remained resilient, even as interest rates climbed. Housing starts in 2022 fell only 3.4 per cent from 2021 and remain well higher than the late 2010s. In previous slowdowns, in the late 2000s and early 1990s, declines in housing starts were far sharper.

Neighbourhoods like West Point Grey in Vancouver cannot any longer see their populations unchanged over decades. The problem of housing in Canada is serious and the scale of the response must match the size of this challenge. The type of future sketched out at the Jericho Lands is part of the answer that cities must embrace. Canada has surpassed a total population of $40 million people. That number will increase significantly as the national government increases immigration levels, which is already putting a lot of pressure on housing. There is an imbalance in Canada: too much demand and too little supply. Yet, we are the second largest landmass in the world. Canada has no choice but to take bold and decisive action to meet this need.