What’s gone wrong with passports, airports and basic federal services? How a perfect storm swamped Canada’s bureaucracy

For months, Canadians who want to travel or newcomers hoping to immigrate have been left behind by short-staffed, slow-to-adapt institutions. The Globe asked the experts how it happened and who’s responsible

By Shannon Proudfood

The only passport office in Ottawa lives in a dingy strip mall that seems ready to collapse from low self-esteem. A sign posted on the exterior doors commands, ominously, “FORM ONE LINE HERE. DOOR UNLOCKS AUTOMATICALLY AT 0700.” The mall now seems to exist only for the unfortunate souls who come to wait. There’s a tiny photo lab that rapidly prints passport photos for people found to be wearing the wrong facial expression or shirt colour, and a dentist office with a large, futile sign asking people not to block the entrance.

On an early afternoon in mid-October, a line of two dozen people is waiting in passport purgatory. The questionably lucky ones at the front have been here since 9 a.m.

Matt Steel, 29, checks with a security guard about his options, with a trip coming up in less than two weeks. The “urgent” line is for people travelling in the next two days, the guard says, so the long line with everyone else is where he needs to be. “I’m already stressed, I can’t imagine two days,” Steel blurts out. Several people standing near him cackle. It is the laugh of those who are already dead inside and pleased to welcome another to their ranks.

Mr. Steel and his girlfriend are going to Las Vegas 10 days from now, “not for the normal reasons,” but to rock climb. He was certain he knew where his passport was, but spent six hours ransacking his place without finding it.

“I knew this was a disaster months ago,” he says, gesturing to the line. “Which is why I haven’t told my girlfriend because I don’t want her to stress. So I’m just trying to get this handled.”

At 1:30 p.m., an employee announces that the office closes at 4 p.m. and anyone who doesn’t get processed will have to start over tomorrow. “We will serve as many as we can up until that time. It’s first come, first served. There are no tickets, there is no getting an appointment to come back,” he says, telling them if they don’t get in today, they need to line up by 6:30 a.m. tomorrow to ensure they get in.

Provincial governments educate your kids, bind up your broken bones, issue your driver’s license, marry you and sell you alcohol and cannabis. Your municipality tickets you if you leave your car in the wrong spot, picks up your garbage, clears the snow off the streets and will put out the flames if your house catches fire.

But for most people, the federal government exists like the Wizard of Oz: distant and obscure, either omnipotent or inept depending on the day. And most of the few areas where the feds do things directly for citizens – passports, immigration applications and air travel – have, for much of this year, been such shambolic disasters that it’s reasonable to wonder what exactly the man behind the curtain thinks he’s doing.

The timing could not have been crueler as the snafus piled up through the spring and summer. The world was finally opening up after the longest two years on record, and Canadians seemed trapped at home because of the extravagant inability of people in charge to anticipate something as obvious as everyone wanting a change of scenery. And there was the federal government, expressing the bland contrition of a store manager soothing an irate customer while not actually solving their problem.

To understand what went wrong, The Globe and Mail spoke to more than a dozen people with knowledge of the policy files at play and the machinations of the federal government and public service. What emerges is a picture of once-in-a-generation challenges brought on by the pandemic, exacerbated by inaccurate forecasts, slow reactions, moribund systems, a tendency to lurch from one crisis to another and a public service that has become top-heavy and overly centralized.

“Good public administration is a combination of poetry and plumbing,” says Senator Peter Harder, who has deep experience in complex policy areas as a former deputy minister in multiple departments, including immigration and foreign affairs. “If all we are at the senior level are poets, you lose the credibility, because the credibility comes from the plumbing side, frankly. We have to get the basics right if we want to talk about the policy issues.”

In other words, why should I hand over my taxes and let you mood board the future of the country if you can’t get me a passport in a reasonable amount of time with minimal annoyance?

The first signs of trouble on that front surfaced in the spring, with massive delays in processing applications from Canadians eager to travel. People began lining up at passport offices in the middle of the night, hours before they opened, and in Montreal, the queues grew so large that police were called to corral them. A cottage industry of “line standers” popped up in various cities, offering to hold someone’s place for an hourly rate.

Last summer’s disastrous effort to get people out of Afghanistan was a high-stakes preview of immigration delays now so protracted that the system has become an impenetrable black box. Pandemic bottlenecks and a decision to pivot Canada’s immigration strategy contributed to a series of backlogs that are still cascading.

Huge security lines at airports, forests of lost luggage and widespread flight cancellations emerged as the next maddening travel gauntlet. Toronto Pearson Airport earned the embarrassing distinction of being the most delayed air hub in the world, with Montreal’s Trudeau International Airport right behind.

Aviation is federal jurisdiction, and opposition politicians gleefully heaped blame on the Trudeau government and its COVID border screening measures. More accurately, it was staff shortages, and hiring and training lags after massive pandemic workforce contractions that were to blame, along with airlines selling more flights than they could handle. But by that point in the bad-news cycle, it didn’t matter. “It’s like Velcro: everything sticks in terms of a sense of, ‘Gosh, can’t you guys get it right?’” says Senator Harder.

What went wrong with the passport section of Canada’s plumbing was actually quite simple, says Karina Gould, minister of families, children and social development: more applications came in than the system could handle, and they came from unusual channels that made things more difficult still.

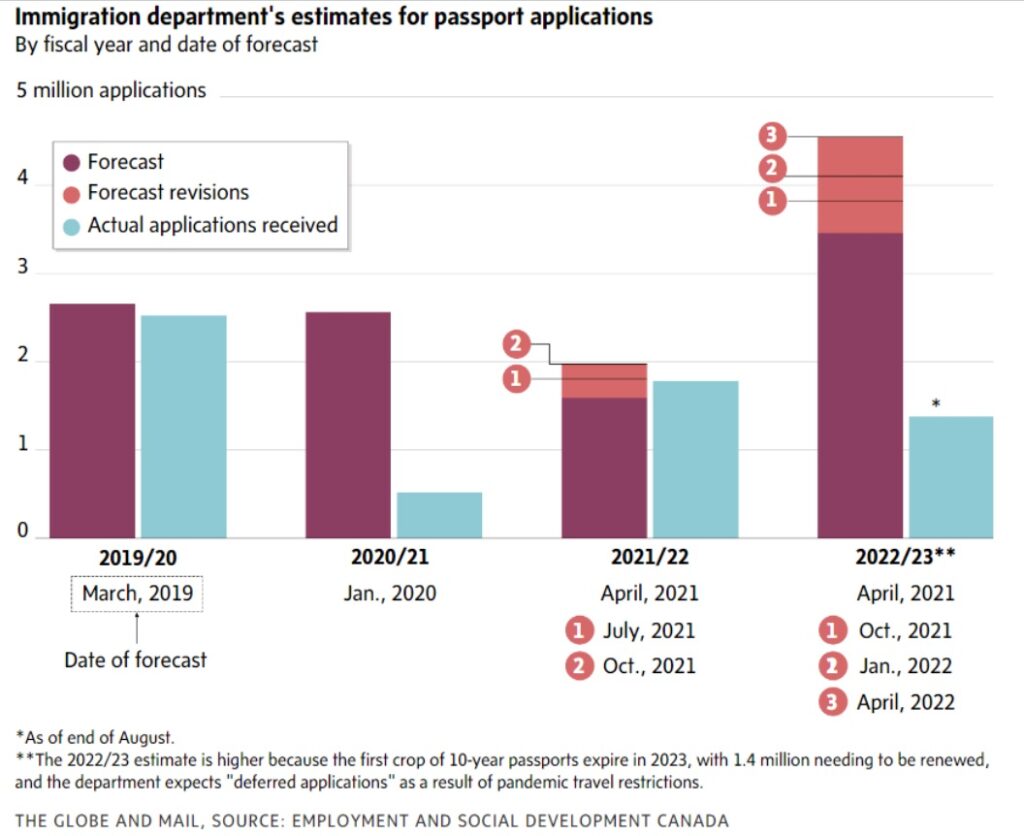

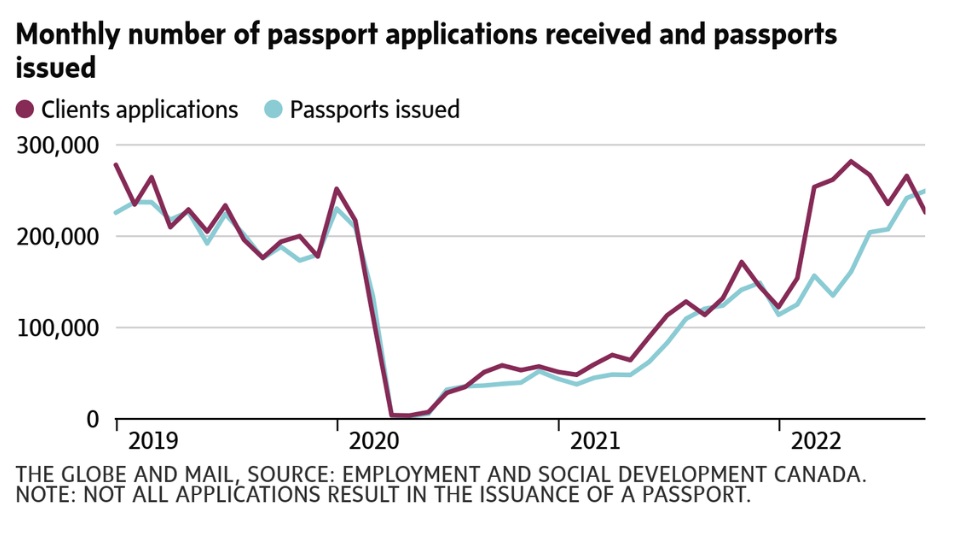

There were 521,000 passport applications in the fiscal year ending in April 2021 while everyone was locked down, and 1.8 million the following year; then between April and September of 2022, 1.5 million applications poured in. “The system had to readjust, but that takes time,” Gould says.

Pre-pandemic, the usual mix was 80 per cent in-person applications and 20 per cent mail-in, but the proportions reversed as everyone did things remotely. Mail-in applications take 40 per cent longer because staff have to open, manually enter and verify everything. About one in four applications have errors, so the applicant has to be contacted for more information or forms sent back, where in person, problems can be corrected on the spot.

Staffing levels in passport processing were already low because they ebb and flow with demand, Ms. Gould says, and in the thick of COVID, staff were moved to where the work was. It takes 13 weeks to train a new passport officer and even more time to hire, so by the time the full scope of the problem was clear, the solutions were months out of reach.

The screamingly obvious question is how the government and public service failed to expect the pent-up demand for travel. Ms. Gould says they did expect it, but they didn’t anticipate how big it would be, or how suddenly it would arrive.

“Don’t get me wrong: what Canadians experienced with passports in the spring and into the summer was totally unacceptable,” she says. “But in February 2022, you still had experts saying it was going to take three years for travel to recover, and then it recovered almost instantly.”

The immigration system also suffered from pandemic congestion, but a different set of circumstances and decisions compounded it.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) had particular problems with remote work because network issues in different parts of the world and privacy concerns led to a loss of staff “horsepower,” says Sean Fraser, minister for the department.

But the bigger COVID impact was in the supply of applicants. With borders closed, few people could get into Canada. The government decided to create a new pool of permanent residency candidates out of temporary residents already in Canada – known as the “TR to PR” stream – in order to hit its population growth targets, Mr. Fraser says.

At the same time, applications continued to come in for people who couldn’t get to Canada, so they piled up, with no way to process and clear them. Canada’s immigration system normally functions like a bucket that is constantly refilled from the top with new applications and drained from a hole in the bottom as people are processed, maintaining an imperfect equilibrium. But COVID border closures nearly sealed the processing hole in the bucket, and the TR to PR program created a second stream of applicants pouring in from the top, so the whole system overflowed.

The effort to settle refugees from Afghanistan and Ukraine further taxed the system by introducing new priority pathways.

But without the creation of that TR to PR program, a country with an aging population and shrinking workforce would have seen its settlement of newcomers grind to a halt, Mr. Fraser says. “This is something that I think we would do again, despite the fact that it would create certain structural challenges,” he says. Canada resettled a record 405,000 permanent residents in 2021 and is on pace for 431,000 this year, he says.

But alongside that, there were widespread labour shortages, clamouring from the provinces to choose and process their own immigrants, and delayed work permits. As IRCC raced to address that backlog, thousands of international students admitted to Canadian colleges and universities were stuck in their home countries without study permits as classes started in September. Next, highly-skilled immigrants were watching their work permits expire before they could apply for permanent residency, forcing them to return to their home countries.

“It’s not so much that we’re doing one thing at the cost of another,” says Mr. Fraser. “We’re doing more of everything, but the increase in demand is simply extraordinary.” He concedes that “surge capacity” is something his department needs to scrutinize.

The study permits delay was so pernicious that in mid-August, the High Commission of India pointedly noted in an advisory that 230,000 Indian students pour $4 billion into Canadian schools. Highlighting “the fact that Indian students have already deposited tuition fees” for the school year, the high commission urged Canadian authorities to speed things up.

The experience of Nicole Yeba, a 33-year-old bilingual communications officer for the Prince Edward Island provincial government, illustrates that Canada’s stretched immigration system has been a hiccup away from disaster for years. Ms. Yeba, was 11 when she arrived to Canada in 2000, and it wasn’t until 2016 that she got permanent residency, after multiple bureaucratic snafus. Now, she’s been waiting nearly three years for her citizenship application to be approved.

“I don’t know what I’ve done wrong, I tried to do all the processes,” says Ms. Yeba. “They keep saying, ‘Oh, we want more people, we’re such a welcoming country,’ but it doesn’t feel welcoming when their immigration process takes forever.”

Mr. Fraser maintains that Canada’s global reputation as a top destination for immigrants is unmarred by slow and uncertain processing. But as Ms. Yeba has learned, when you can’t get in the door despite doing everything you’re supposed to do, eventually you start to wonder if what’s on the other side is worth the wait.

Aside from the specifics of the service snarls, close observers of government and the public service see big, long-standing weaknesses underlying all of it.

One is the complexity of departments and policy areas, which means when something goes wrong, sorting out accountability is “like trying to grab smoke,” says Donald Savoie, Canada Research Chair in Public Administration and Governance at the Université de Moncton. “Nobody in the government of Canada or in the public service at the personal level would say, ‘I own this mistake, it’s my mistake.’ Why? Because in most cases, it’s not their mistake,” he says. “There’s so many hands in the soup that you can’t really say who screwed up.”

He has studied and written extensively on the public service, and he detects a growing “fault-line” between those who deal with clients or services and those who work in the more rarefied world of policy. The public service has become top-heavy, Mr. Savoie says, with enormous growth in the number of senior managers: Too many poets and not enough plumbers.

In 1975, 72 per cent of the federal public service worked outside the National Capital Region, he says, but now, that proportion is just 57 per cent. Many senior managers have never worked in regional or local offices, and Mr. Savoie believes it’s all led to a dulling of the collective senses. “The world that they know is the world they know in Ottawa,” he says.

To Alex Himelfarb, the country’s top bureaucrat as clerk of the privy council from 2002 to 2006, there is a circular nature to all of this that means the problems of this spring and summer are likely to give rise to more of the same in the future. These neglected processes only seem to hit the political radar when they fail, and because of that, he says, they’re bound to fail again.

“Most public services are taken for granted, until they break,” he says. “And then when they break, we think, ‘Is government competent enough to fix it? Look how bad things are.’”

Investing in the kinds of hidden, unsexy, but necessary upgrades that make things run smoothly even when there is enormous volume is a very difficult political sell, Mr. Himelfarb says.

He walks this out with a thought experiment: if the government announced tomorrow that it was spending tens of millions to improve IT or other backroom services, what would be the political reaction? “The incentive for investing in these kinds of system improvements is not zero,” he says. “It’s some minus number.”

As the embarrassing news stories piled up, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau eventually announced a task force to improve government services. “I do want to say that nobody should be congratulating themselves for doing their jobs,” said Marc Miller, co-chair of the task force and minister of Crown-Indigenous relations, when the group offered a progress report at the end of August.

In an interview, he repeatedly referenced the role of task force members in “keeping each other honest” and looking at hard truths, but he wouldn’t go into more detail than that. “I can’t share some of the conversations that were quite frank and had in the middle of cabinet because they can be quite cutting and frank – and they need to be in order to be a minister in a G7 country,” he says.

The next customer service irritation between Canadians and their federal government is set to be the NEXUS program that allows pre-screened travelers speedy clearance between Canada and the U.S. It’s been shuttered by a protracted jurisdictional dispute, and the backlog of applications had reached 332,582 as of Nov. 1.

In the meantime, things have smoothed out at the airports and passport turnaround times have improved, but Service Canada warns of longer than usual waits and no guarantees. If you’re travelling in the next few months, your safest bet is still to stand in an interminable queue.

By late afternoon in passport purgatory at the Ottawa strip mall, the line that had shrunk for a time has swelled again with a few cocky or oblivious latecomers (the other tenants evidently tired of the arrangement, because the next week, the line-up moved outside the mall). The security guards let several people into the passport office at once and then, with Mr. Steel next to be admitted, the line stalls.

By 3:45 p.m., the comradely chatter fades to a tense silence punctuated by the occasional sigh or muttered curse. One well-dressed woman walks away, announcing that she just doesn’t want to hear the staff tell them it’s officially over.

At 3:55, a security guard closes one of the doors with a merciless metal clank. A woman near the front of the line mutters, “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

“I’ve waited this long, I’m just gonna chill for the next four minutes,” Mr. Steel says to no one in particular. When the second door clanks shut at 4 p.m., he is standing right in front of it.

He returns in 6 a.m. darkness the following day to find seven people already waiting, the first of whom arrived at 5 a.m. Following a series of last-minute issues with his documents, it isn’t until 11 a.m. that Mr. Steel hands everything over to a passport officer. He leaves a short time later with an appointment to pick up his new passport, two days before his flight to Las Vegas.

All told, he waited in line for nine hours to solve the problem he hopes his girlfriend never has to know existed. Canada really needs to have its plumbing looked at.

source: apple.news